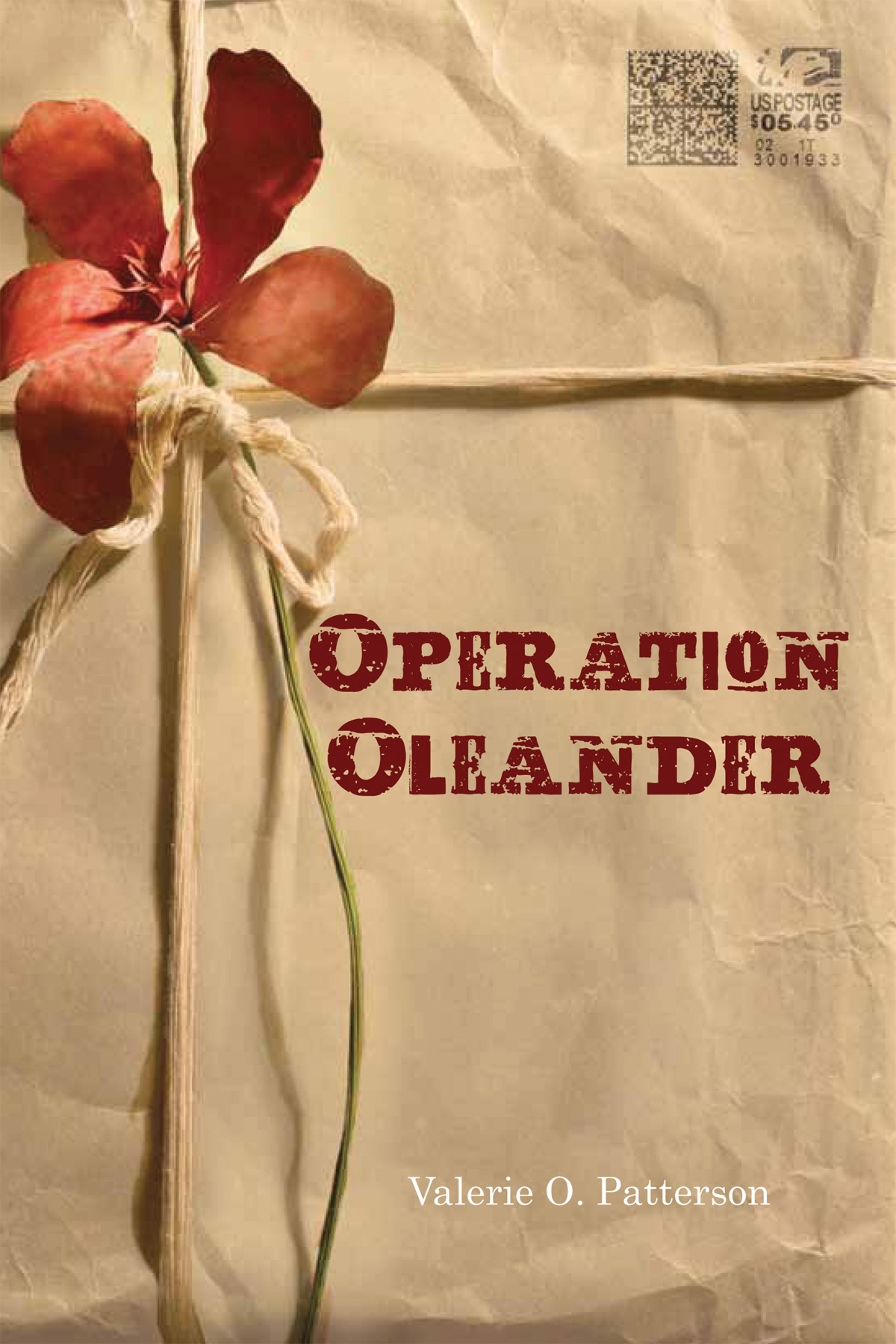

Valerie Patterson is the author of Operation Oleander. The following is a complete transcript of her interview with Cracking the Cover.

Have you always wanted to be a writer? Why?

Ever since I was a child, yes, I have wanted to be a writer. I love language and imagery, the way words sound on the page and how words evoke emotion and understanding. My parents and grandmother read to me and supplied me with books. Summers were measured by trips to the book mobile. I started writing poetry in elementary school. In fourth grade, I wrote a book of limericks for a favorite teacher who had a touch of the blarney. I also began writing short stories (mostly about horses and other animals). In college, my emphasis was poetry. Novels came only later, after graduate school and early years of a career in a different field (law).

To me writing, unlike anything else, is how I make sense of the world and how I connect with it. I’ve used the following quote before, but it continues to resonate with me: “In our desire to understand, in the constant movement between ourselves and others we may find redemption.” Melanie Rae Thon, as quoted in Letters to a Fiction Writer, edited by Frederick Busch.

Why write for young readers?

I attended a conference at Vermont College of Fine Arts last summer. Tim Wynne-Jones, award-winning author of Blink and Caution and many other books, said he thought the difference between literature for adults and literature for young adults is that fiction for young readers is about learning to cope with the world and life. In contrast, literature written for adults sometimes seems as if it’s written to help people cope with death, or letting go of the world, instead of embracing its possibilities. I think I write for young readers because I have hope for the future. Not a Pollyanna style hope—but a hope born of faith. I also think the young adult years are interesting and intense and I seem drawn to those years in my writing. I have a half-finished manuscript for adults, but it doesn’t call to me to be finished.

I also like Madeleine L’Engle’s quote. “You have to write the book that wants to be written. And if the book will be too difficult for grown-ups, then you write it for children.”

Where did the idea for OPERATION OLEANDER come from?

Several years ago I read the novel QUAKING by my friend Kathy Erksine. The book is about a foster child who ends up living with members of the pacifist Society of Friends. After reading the book, I wondered about a different situation. What is the impact of war on the child of a military family? How does that shape his or her views of the world, the war? And what happens if the unthinkable occurs? Starting a novel with “what if” seemed harder to me than a book in which the character just comes to me. I’m more of a “discoverer” than a “plotter.” As a result, I struggled with the book. At first, I sent Jess’s dad off to the conflict zone and then had her mother take the children off-base. The story unraveled and became more about her mother’s depression than about what Jess was doing. It took me several drafts and a meandering course to finally begin to narrow in on the heart of the story. This is a story about connections with her family and friends and the larger world. Then I started over in first person. That’s when I heard Jess’s voice.

Are elements of it based on real events?

They’re not based on any one event, no. But articles have been written about charitable giving and its sometimes-unintended consequences. For example, putting in wells in Bangladesh seemed like a tremendously helpful thing to ensure poor people would have access to fresh water. Unfortunately, due to the geography of that area, the wells also produced high levels of arsenic in the water. News articles about protests at military funerals also seeped into the story.

How much research did you have to do?

I grew up near a navy base in Florida, so I had a picture in my mind of what the Army post would look like in my fictional part of Florida. I ended up visiting another Navy base while I was writing the book, so I had even more images to draw from in depicting the physical layout of a military installation. My dad was a veteran, and I went to school with military dependents. I felt that I had an understanding of some of what their lives were like. More recently, I read letters from soldiers to their families, and blogs about military life.

To make certain I had no major blunders, I asked a military family member to read the book through for errors. She read not just for factual mistakes but nuances or anything that rang untrue. My factual mistake, easily remedied, was that, while the Navy has “bases,” the Army has “posts.” What encouraged me was the feedback that I had the nuances correct of what living on base was like, and what differences might be perceived between the children of officers and the children of enlisted personnel.

Jess is a complex character. How did she evolve?

That’s a hard question to answer. She did evolve, from a passive character who only was acted upon in early drafts to one who also had her own ability to act. She finds a way to move forward to meet what she believes she must do as a person in this world

OPERATION OLEANDER isn’t really a happy book. Was it difficult to write?

OPERATION OLEANDER isn’t really a happy book. Was it difficult to write?

That’s an interesting observation—that this isn’t a happy book—but I hadn’t thought of it like that. Truly difficult things happen. A charitable effort goes awry, a parent is injured, and another’s parent is killed. Friendships grow strained and change forever. So, you’re right. In that real sense, it is a not a happy book. For me, though, the ending is hopeful. So I see this as a hopeful book. We all endure difficult situations in our lives. The key is how do we approach the difficult situations? How do we find our way? How do we love one another?

As for writing the book, yes, I struggled to find its heart and to understand Jess. As a person, I hate conflict. In fiction, though, a book without conflict is dead. Nothing happens that the reader cares about. So, the saying goes, we have to put our characters in difficult situations, and then we have to make things worse. And worse. Only then can we see what they are made of, and what we might be made of, too.

In one of the drafts of OPERATION OLEANDER, I skipped over the funeral scene completely. It was too hard to write, too painful, so I tried to simply avoid it and start the new chapter in a different place. Of course, I had to go back and write that scene. Jess had to endure that situation, which was compounded by the anti-war protestors who chose the funeral as their protest venue. As filmmaker Akira Kuroswa says, “To be an artist means never to avert your eyes.” You have to be prepared to go to the dark place and write about it.

Have you had any response to your book from military families?

Clarion and I are reaching out to military families in a number of ways, and I’m keen to hear from young readers on what the story meant to them. There’s a way to contact me through my website at www.valerieopatterson.com.

Why do you think young readers enjoy your books?

I hope they like them because they can identify with a character. Even though their lives may be very different, if they can imagine what it must be like to have a parent deployed or to face the unthinkable, they can become more empathetic, more thoughtful. Sometimes, too, fiction puts a voice to fears we have and illuminates strengths that we don’t know we have, but we can believe we do because we see characters find internal strengths and overcome obstacles.

Looking back, how has your writing evolved?

I used to write mostly poetry and now I write mostly prose. I hope I bring poetic elements to my writing—imagery, word choice, rhythm. I’m still exploring different genres, such as fantasy and mystery, different age groups. I’m still learning, still finding my way as a writer.

What are you working on now?

I’m revising my first attempt at a fantasy novel. It is layered and complex, and I’m finding it a challenge to make the world believable and to make the plot move in a logical and compelling way.

Is there a book from your childhood that still resonates with you today?

I still have the Golden Treasury of Poetry on my shelf. The binding is frayed and a few pages are missing, but I still take it out and read it. I still like Jo from LITTLE WOMEN for her spunk and her writing dream.