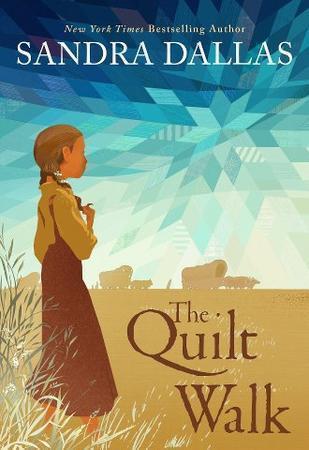

Sandra Dallas is the author of 11 novels for adults, 10 nonfiction books and countless articles as a reporter for Business Week. “The Quilt Walk” is her newest novel and her firs for children. Below is a complete transcript of her interview with Cracking the Cover.

You’re the author of a number of books for adults. Why did you decide to write for young readers?

A friend told me the title story of my history of quilting in Colorado and the Mountain States, The Quilt That Walked to Golden, published in 2004, would make a good children’s book. I’d never considered writing for children, but I was intrigued and agreed that the story of a little girl walking to Golden might work for children. As I was between books with no idea of what I would write next, I decided to give it a try. That draft wasn’t very good, and it was the wrong length for a children’s book, so I put it aside and forgot about it until I was approached by Amy Lennex at Sleeping Bear Press, asking if I’d ever considered writing a children’s book. Amy saw possibilities in the manuscript, and I decided to rewrite it. Amyis a superb editor. She taught me how to write for children.

Where did the idea for The Quilt Walk come from?

The Quilt Walk is based on a real event. In the early 1860s, Thomas Burgess came west to strike it rich. He didn’t but realized there was money to be made in erecting commercial buildings. So in 1864, he and his wife, Mary Ann, and daughter, Alice, along with his brother and the brother’s wife, came west. The men filled the covered wagons with building materials, so there wasn’t room for trunks of clothing. The men told their wives they could take only what they could wear. So the women put on all their clothing and walked (you didn’t ride much in oxen-drawn covered wagons) all the way to Golden. When the clothing wore out, they cut it up and made a quilt—known in the family as “the Quilt That Walked to Golden.”

What were the challenges writing this story? What were the highlights?

I had only a few facts about the Burgesses and realized the story would be mostly fiction. So I changed the names. Alice Burgess became Emmy Blue Hatchett. I had to start thinking like a 10-year-old, something I hadn’t done in 60 years. I had to cut out much of the detail that I would put into an adult book and concentrate on writing simpler sentences. The highlight was that I discovered I loved writing for children.

How much research was involved?

I’ve written both fiction and nonfiction books about the west, so I already knew much of the background. But I had a heck of a time finding how you manage oxen and the commands you give them.

Where did Emmy Blue come from? Is she based on anyone you know?

Emmy Blue is entirely fiction, although I’m sure my childhood friends sneaked in there somewhere.

I really liked how you incorporated not only Emmy Blue’s parents’ relationship but the relationships of other adults into the story as well. Why was that important?

Because my adult novels deal with women’s issues as well as friendship, I wanted The Quilt Walk to be more hard-edged than just a children’s adventure story. I wanted readers to think and learn as well as enjoy themselves. So I added domestic abuse and women’s lack of options in the mid-19th century. These don’t dominate the book, of course, but they are part of its fabric.

Do you quilt?

I am a poor quilter. But I love quilts, especially the old ones, because they are women’s art. And I collect antique doll quilts.

Why was quilting so important to the women during this time period?

Why was quilting so important to the women during this time period?

Women were not encouraged to become fine artists, so they put their artistry into every day objects. They could have made big patch quilts, but instead, they chose to make them using intricate designs. And quilting involved friendship—trading scraps and patterns, getting together to stitch. Life was hard in those days, and quilting was about beauty and friendship.

You tend to write historical fiction. What about it appeals to you?

I’ve always loved history. I was born on a 25-acre farm in Virginia, and Mom took us to all the historic places before we left for Colorado when I was six. In Denver, she made sure we visited the historic building, although they were located in the slums. When I was first married I lived in Breckenridge, a mining town-turned ski area, and met many of the old miners. And I covered hardrock mining when I was with Business Week. I’ve written 10 nonfiction books, most of them about the West.

Looking back, how has your writing evolved?

I went from journalism to nonfiction to journalism to adult novels to children’s books. I’m not sure where I go from here. Oddly enough, there is a connection. It’s all about words and how you put them together.

Why do you think readers find your books so appealing?

I think they relate to the friendship and the connection women make with each other in my books—and to the women’s issues.

Is there a book that resonated with you as a child?

Of course, I loved the Little House books. My sister’s favorite book was Smiling Hill Farm about a family that goes west and the generations who lived on the farm, and I read that many times. I also liked Little Britches, which was about a farm boy growing up in Colorado. When I was older, I read all the Nancy Drew books. Libraries wouldn’t stock them, and I don’t know why, because Nancy was a wonderful role model. She thought for herself, wasn’t afraid, didn’t depend on men, and solved mysteries. In most of the children’s books back then, girls were incompetent. They fell down, screamed at the wrong time, made foolish decisions, and had to be rescued by boys.