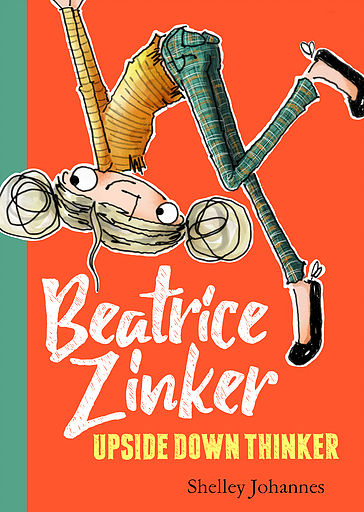

Shelley Johannes is the author of Beatrice Zinker Upside Down Thinker. The following is a complete transcript of her interview with Cracking the Cover.

Shelley Johannes is the author of Beatrice Zinker Upside Down Thinker. The following is a complete transcript of her interview with Cracking the Cover.

Before becoming an author-illustrator you were an architect. What prompted your move from one to the other?

Though I still love architecture today, architecture was never my dream. As a shy, art-loving high school student, I chose architecture because it was a safe, quantifiable career option within a creative field. I always wanted to be a writer or an artist, but I couldn’t envision what that would look like, or how I could make that happen. There were so many barriers in my mind—from my limited life experience, to my location, to my quiet personality. The world of children’s books was completely off my radar.

Just before I became a parent, I transitioned out of architecture and settled into a variety of freelance opportunities that offered more flexibility. Working on my own schedule allowed me to spend lots of precious time with my kids while they were young. Reading with my own children ended up being the turning point. One day, with my two-year-old on my lap and How I Became a Pirate in my hands, I fell in love instantly. I realized that children’s books were a perfect combination of word and image that I’d never considered before. Doing something about that revelation was still a long way off, but my vague career dreams suddenly had clarity.

Why do you write/illustrate for young people?

When I was a kid, one of my biggest fears was that I’d grow up and forget what it feels like to be a kid. I kept a journal for years and years in an attempt to thwart that forgetfulness. Though my own kids might say otherwise, I’ve tried to be true to the younger version of myself. Kids are masters of wonder. They experience life with their whole selves. Even while wrestling life’s big things, small moments still impress them. Complexity and wonder coexist so beautifully in young people, and I can’t imagine writing for any other audience.

If you could only be a writer or only be an illustrator, which would you choose?

Writing and drawing are both second-nature, so that’s a really tough question. If forced though, I would have to choose writing. Not writing would be physically impossible for me. I’ve gone through periods of life (years even!) without drawing, but I doubt I’ve gone a day without writing. My brain is wired in words. As I go about my day, it’s constantly composing a narrative. Even when there’s no way to document them, words never stop lining up and moving themselves around.

Where did the idea for Beatrice Zinker, Upside Down Thinker come from?

Where did the idea for Beatrice Zinker, Upside Down Thinker come from?

I spent a lot of my life trying to camouflage the things that made me different. Even after I knew I wanted to make children’s books, I struggled, not knowing what to write about. One day I ran across a quote from Joss Whedon that said, “Whatever makes you weird is probably your greatest asset.”

The truth of that stayed with me for days and days.

The next time I was at my local library, Beatrice appeared for the first time. I was standing in front of the New Books display, trying to decide how many books I could take without being a complete jerk, when she dropped from the ceiling in her ninja suit, ready to steal them all and make a quick getaway before being apprehended by library secret service. She was a manifestation of my love of books and my guilty conscience, and I knew immediately—way before she had a name—that Beatrice was my weird.

What came first, the text or illustrations?

For me, text and image are very connected, and it’s difficult to separate them. The mental image of Beatrice, dropping from the library ceiling in a ninja suit, came first—followed by a picture book dummy. On a page of that early draft, Beatrice was on an elevator ceiling, paired with the words, “Lucky for Beatrice, she did her best thinking upside down.” It epitomized Beatrice as a character, and—thanks to my agent—eventually inspired the concept of Beatrice as a chapter book series.

A text/image combination inspired many moments of the story. The whole first chapter, for instance, sprang from an illustration of Beatrice’s ultrasound picture and the words “Beatrice, however, had been different from the very beginning.” There was a point in the journey when I had to lock away by art supplies for a bit, so I could concentrate on the story. But if I ever lost my way, or got stuck, sketching Beatrice and her silly antics always brought me back.

Beatrice likes to look at things differently. How did her character develop?

Sometimes a character appears in your head with certain truths attached to them. When Beatrice showed up in my imagination, she was upside-down in a ninja suit. It wasn’t a conscious decision to make her think differently—it was just a piece of who she was. I couldn’t have put words to it, but like Beatrice’s ultrasound picture, Beatrice—as a figment of my imagination—was different from the very beginning, too.

It was fun to figure out how to put her in the right context to show that off, and to make it relatable. Beatrice started as a book thief in a picture book, then after spending a couple months in a convoluted plot in a boarding school, she finally found her home in a right-side-up family and very recognizable life. Within that familiarity, it was even more fun to explore all the sides of her upside down personality.

Are you more like Beatrice or Kate?

Though I hate to admit it (sorry, Kate!)—I’m a bit of both.

I’m an older sister, so as a kid, I often played the role of Kate. In school, I was a perfectionist who cried when I got an A minus. At home, I governed the entire narrative of our Barbie realm to my advantage, and was horrified when my little sister told strangers she wanted to marry her blanket.

But deep down, outside of the birth-order roles we sometimes fall into, I’m definitely more of a Beatrice. I spent a lot of time upside down as a child, planning how I would arrange the furniture if I could live on the ceiling. When I was younger, I was afraid to lead with that side of myself. My brain is a scattered, messy, intuitive place—I no longer feel like I need to downplay that. Celebrating it is much more fun.

Why do you think young readers will be attracted to Beatrice’s story?

I hope the quirk of Beatrice’s personality, and the playfulness of the illustrations, will make it fun and easy for young readers to dive into her story. The ninja suit, spy moves, and a secret operation don’t hurt either. Beyond that—Beatrice is a little different and doesn’t fit in. She feels like an outsider at home, and is afraid she’s losing her best friend. Most of us, at any age, can relate to those feelings—but young people, especially, know them well. I hope Beatrice inspires kids to enjoy all the upsides of being themselves—and to give others the freedom to be themselves, too.

What are you working on now?

The second book in the series comes out in 2018, so I’m wrapping up my first round of edits for book #2! Hanging out with Beatrice always makes me happy, and there are two new characters—Sam and Wes—that I can’t wait for readers to meet.

Is there a book from your own youth that still resonates with you today?

Anne of Green Gables will always be the book of my youth, but I’ve been talking about Anne a lot lately, so I’m going to choose another one that still rings true. Even though I don’t remember most of the story details (I’m not a plot person), The Outsiders is never far from my mind. I was haunted, especially as a young person, by Robert Frost’s poem and the idea that “nothing gold can stay.” The wish to stay gold has remained as an internal anthem all these years. I’m sure it’s a huge reason I love writing for young people. There’s a line in Beatrice that says, “Nothing was more official than glittering gold lettering.” It’s my tiny nod to Ponyboy.