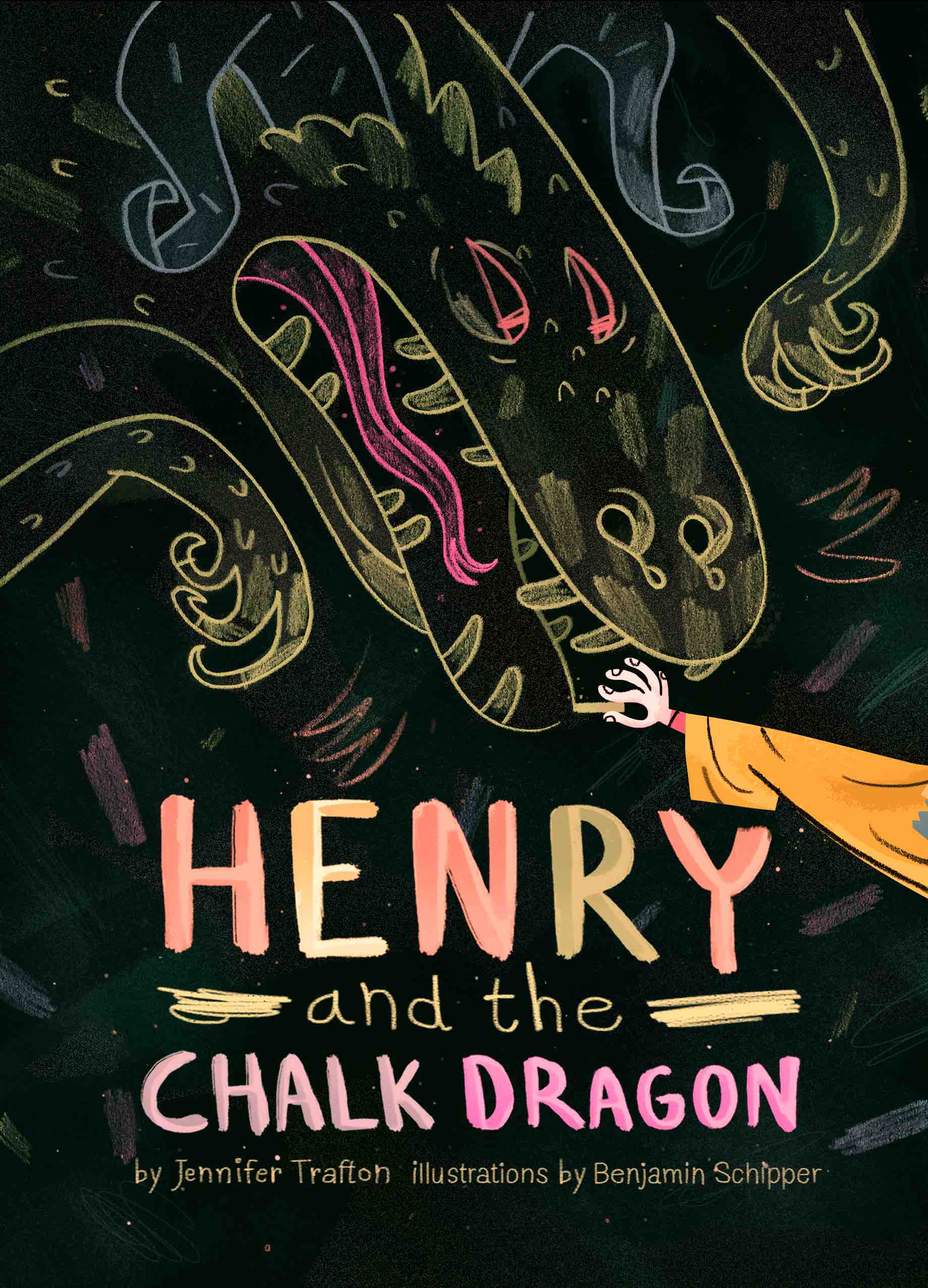

Jennifer Trafton is the author of The Rise and Fall of Mount Majestic and Henry and the Chalk Dragon. The following is a complete transcript of her interview with Cracking the Cover for Henry and the Chalk Dragon.

Jennifer Trafton is the author of The Rise and Fall of Mount Majestic and Henry and the Chalk Dragon. The following is a complete transcript of her interview with Cracking the Cover for Henry and the Chalk Dragon.

Why do you write? Why specifically for young people?

The author Susan Cooper once said we’re all at the mercy of the imagination we were born with—I’ve got an imagination that needs to spill out of me in stories, and they happen to be the kind of stories that have buried giants, walking trees, poison-tongued jumping tortoises, runaway dragons, and children with wild imaginations at their center, because those are the kind of stories I most enjoy reading. I also just find children endlessly fascinating as human beings. I love their fresh perspective on the world, their lack of cynicism, the fantastic ideas they dream up, and their embrace of silliness as well as mystery. I love the questions they ask.

For many years, I tried desperately to be a grown-up and to pursue some sort of normal grown-up career with a paycheck and a retirement fund and all of that, but alas! The pull of giants and dragons and ten-year-old heroines in eccentric hats was far too strong, and I walked one day into the children’s section of the bookstore, spread my arms wide, and bellowed (at least in my heart), “These are my people!” After that, my fate was sealed. So I write “for children” because I feel like, at the level of the imagination, and in the stories I love to read and love to write, I’m one of them.

What is your creative process like?

Messy, undisciplined, unpredictable, and plagued by alternating extremes of joy and terror.

Where did the idea for Henry and the Chalk Dragon come from? Henry’s imagination knows no bounds. How did his character develop?

My first book The Rise and Fall of Mount Majestic began with a situation that made me laugh—the idea of a giant buried underground with people living on top of him, unaware. Henry and the Chalk Dragon began with a character who popped into my head, whole and already named, and demanded that I follow him on his adventure. At the time I was enamored with Man of La Mancha, the musical version of Cervantes’ Don Quixote (remember the song, “To dream the impossible dream”?), and I loved the idea that Don Quixote’s crazy vision of himself and his world was as ennobling as it was eccentric—that his mad dreams of being a knight, following a quest, fighting giants (who were really windmills) somehow burrowed down to some deeper truth about life than those who made fun of him could understand. And it made me think of how children play—at least how I played!—their imaginations transforming a cardboard box into a cave or a pirate ship, a bed into a mountain, a bathtub into an ocean, a homemade costume into a knight’s shiny suit of armor.

Henry was my eight-year-old Don Quixote, and I wanted the world around him to sizzle with magical possibilities. I wanted him to see a different layer of reality to everything—hence all the similes in the book. I also wanted to treat Henry’s imagination, as wild and wacky as it is, with total seriousness, so that his fantasy is the reality. The story goes a little crazy because—well, have you ever listened to a story made up by an imaginative eight-year-old boy?

Henry is an artist. Do you draw?

Henry is an artist. Do you draw?

I have loved to draw even longer than I’ve loved to write! I drew all the time when I was growing up. During high school I wrote and illustrated a picture book and sent it out to a whole bunch of agents and publishers, and it was (rightly) rejected by all! But I had so many other interests that in my 20s, art took a back seat—except during hard or stressful times when drawing was my therapy.

It’s only been in the last five years (actually during the writing and revising of this book) that I’ve found the courage to say, “This art thing isn’t going to go away. It runs too deep in me. Even if I’m not going to be a professional artist by trade, I am still an artist because I love to create.” So I began posting art and hand lettering on Facebook and Instagram as a kind of discipline for myself so that I would more draw regularly. I accepted commissioned work, opened an Etsy shop, and generally gulped down my fear enough to say to the world, “Hey, I’m not just a writer. This is part of who I am too.” That took a big step of bravery for me, and in that sense my journey has mirrored Henry’s.

What’s your superpower?

I am the Superworrier. No kidding, I really am the best worrier that ever lived. If there’s nothing to worry about, I invent worries. I worry about worrying.

There are lots of fun names throughout the book (Penwhistle, Rockbottom, Pimpernel, etc). Where did they come from?

I love naming characters, but I rarely have an interesting answer when people ask, “How did you come up with the name . . .?” I just play around with words, fragments of words, existing names, and letter sounds until I come up with a name that feels like the character. Charles Dickens is my hero when it comes to fictional names. In this book, Henry Penwhistle is a play on Pendragon (the surname of King Arthur), Jade Longswallow is a play on Longfellow (the poet), Oscar Rockbottom made me laugh because Oscar wants to be a paleontologist and likes rocks, and Miss Pimpernel got her name because I needed something flower-like yet noble and adventurous-sounding.

You teach writing. How does that influence your own work?

Teaching creative writing has been my open door into the imaginations of kids (I teach 8- through 14-year-olds regularly, both locally and online). I love their worlds of talking cats, candy cities, portals, ninjas, aliens, bizarre creatures, and extravagant plots. I love to catch them before anyone has a chance to squeeze their creativity into a box yet. I love their misspelled, discombobulated eloquence; it inspires me.

As a teacher, I craft my classes according to my belief that play is at the heart of creativity—free, unselfconscious, uncritical imaginative play. That’s a whole lot easier for kids than it is for us grown-ups who are so hung up on being right and respectable all the time. And so, as I teach my students to play with words, I am constantly reminding myself of what I have to do as a writer, in spite of all the inner resistance my grown-up brain throws in my way. I have to relearn—and relearn and relearn—how to let my imagination loose to play.

What are you working on now?

I’ve been bouncing back and forth between several stories for the past few years, each progressing but not ready to come out of the oven yet. I think one of them has finally emerged as the one I’m supposed to finish next. All I can say about it is this: if my first book began with a situation that made me laugh and my second book began with a character that swept me up in a quest, this one begins with a setting that enchants me.

Is there a book from your own youth that still resonates with you today?

How can I pick just one book?! If you ask me tomorrow, or the next day, I’ll give you completely different answers, but let me choose one that has echoes in Henry and the Chalk Dragon: Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass (okay I cheated—that’s two, but they’re a pair). “Jabberwocky” is one of my favorite poems in the English language. I love Carroll’s reckless, joyful dancing with words and his willingness to thumb his nose at a world that insists, This is how life is, and to push the boundaries of reality. Like Don Quixote, his madness has the ring of truth, and I can’t seem to shake myself free of mock turtles and vorpal swords, cabbages and kings. I hope I never will.