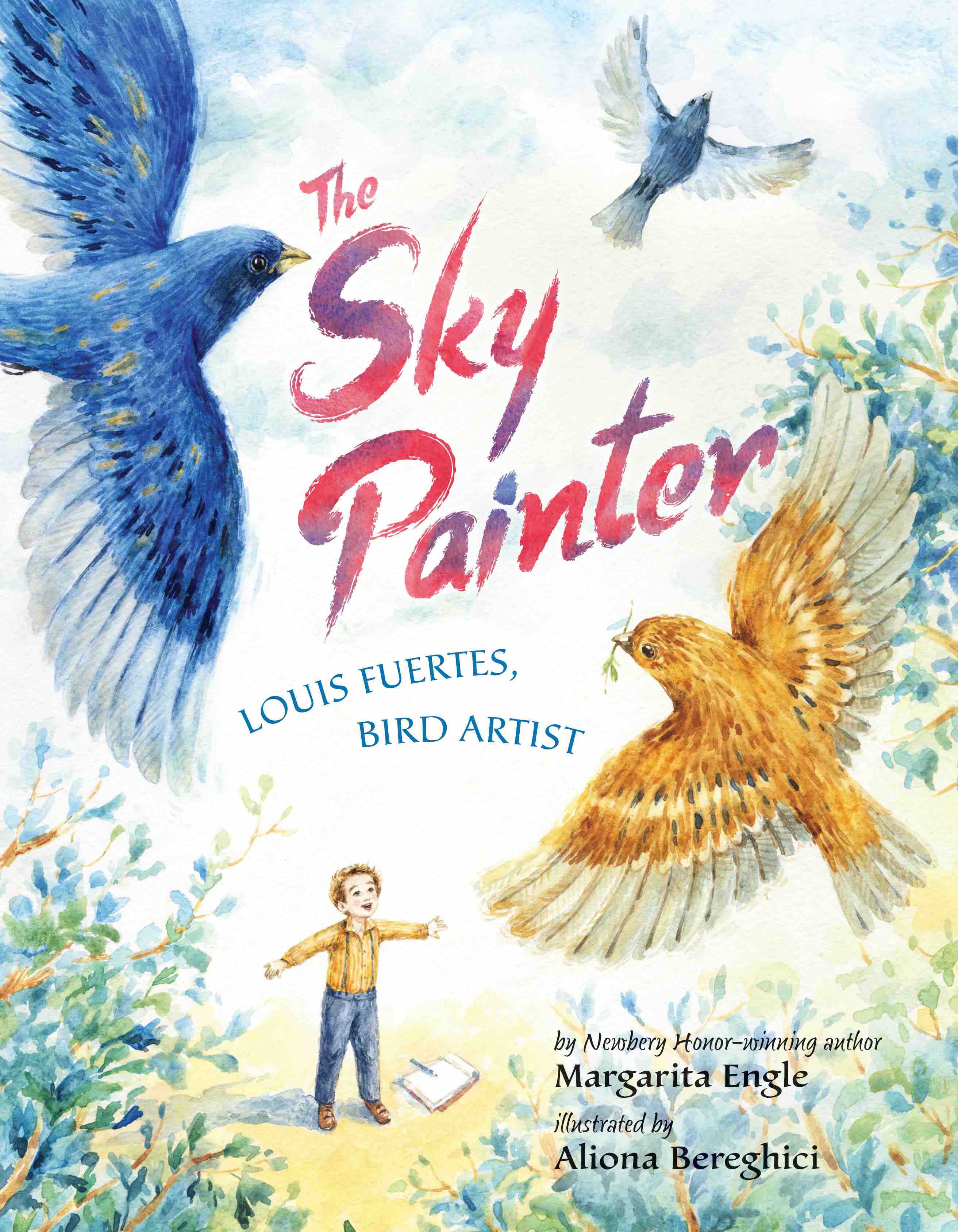

Margarita Engle is a Cuban American poet and novelist whose work has been published in many countries. Her books include “The Poet Slave of Cuba,” “The Surrender Tree,” “Summer Birds: The Butterflies of Maria Merian” and “The Lightning Dreamer, Cuba’s Greatest Abolitionist.” The following is a complete transcript of her interview with Cracking the Cover for her latest book, “The Sky Painter: Louis Fuertes, Bird Artist.”

Why do you write for young people?

Children are the conservationists, peacemakers, scientists, artists, and dreamers of the future. A chance to communicate with the future during my lifetime is amazing. Children are also creative thinkers. They’re not surprised by a mixture of history, art, science, and poetry.

Where do your ideas come from?

I read voraciously. I’m a botanist and agronomist as well as a novelist and poet. Sometimes, while I’m reading about natural history or cultural history, I come across an astounding accomplishment by someone who is not well known. I begin to wonder why I didn’t learn about this person in school. Too often, the obvious answer is that the amazing person was a minority or a woman, a member of one of the groups that have been overlooked by historians.

What about Louis Fuertes’ story appealed to you?

He was an independent thinker. He didn’t kill birds and pose them like Audubon, but challenged himself to learn a new skill. He decided to paint faster, so that birds could live. Pioneering the painting of living birds in flight seems normal now, but a century ago it was a daring, innovative idea. People who think creatively are great role models for children, who will become the wildlife conservationists and other problem solvers of the future.

Why did you choose to tell his story through poetry?

I wanted The Sky Painter to show Fuertes’ whole life, not just one moment. In order to do that, I needed a certain amount of detail, but I didn’t want to lose the spirit of wonder in each moment of discovery. The natural solution was to link short poems that progress as he ages. Even when he was a small child, Fuertes already knew that he wanted to be a bird artist. He also knew that he wanted to help birds. I found it fascinating to follow him into adulthood, pursuing his dreams.

Does poetry limit you or open doors when telling a story?

Does poetry limit you or open doors when telling a story?

I love the flow of free verse. It’s such a versatile form that it allows me to include the emotional essence of a story, while omitting many of the facts and figures that might make that same story inaccessible to young children.

Why do you think your books appeal to young readers?

I hope it’s because poetry and science are both natural aspects of every child’s inherent spirit of wonder. Fantastic illustrators help too!

You’ve been awarded numerous honors. Does that put added pressure on you when you work on/release new books?

It’s an odd combination of pressure and opportunities. I have alternating moments of confidence and timidity. The best way for me to proceed is by throwing my heart into each story, without worrying about whether it will ever be published, reviewed, acclaimed, etc. I love the actual process of researching and writing about subjects that fascinate me.

What are you working on now?

In August my verse memoir will be released: Enchanted Air, Two Cultures, Two Wings. I’m also continuing to work on picture books about other great Latinos who, like Fuertes, have been forgotten by history.

Is there a book from your own childhood that still resonates with you today?

I was a horse crazy daydreamer, so I loved The Black Stallion. Childhood summers in Cuba with my extended family gave me a love of the island’s culture as well as tropical nature, but there were no multicultural children’s books yet, so I sneaked into the adult section of the library to read books written by people from different countries. At the age of ten, I read Things Fall Apart, by Chinua Achebe. I never read another children’s book until I had children of my own.