Jane Nickerson is the author of “Strands of Bronze and Gold.” The following is a complete transcript of her interview with Cracking the Cover.

Jane Nickerson is the author of “Strands of Bronze and Gold.” The following is a complete transcript of her interview with Cracking the Cover.

Why do you write?

Because ever since I was little I’ve had a feel for words that has to come out in writing. Even when I was playing with my Barbies, I would imagine the dialogue between them and describe their setting and their clothes. (They had lots of fashion shows.) I absolutely love finding the perfect word for the perfect sentence to convey the atmosphere, emotion, character, picture, or thought I want to bring across. I’m a story-teller as well, but only in the written form. I need to share words and stories with other people.

Why specifically for young readers?

Lots of reasons. When I read for fun (which is all the time), I devour YA or middle grade fiction. To me, it’s more creative, more interesting, takes itself less seriously, and is less full-of-itself than grown-up literature. When you read it, or write for it, you don’t have to pick one genre and stick to it, since YA and middle grade covers all sorts of genres. It seems to fit my tastes and my brain better as well. When I was a teenager myself, we didn’t have specific YA books. I thought I had to graduate from kids’ fiction to adults’, and so I did. Although I enjoyed the lighter grown-up novels, when I took a children’s literature class in college, I thought, You know, I still like these. And so from then on, I gave myself permission to read THE GRAVEYARD BOOK and FIVE CHILDREN AND IT or anything else that caught my eye regardless of its age level. Also, I really like kids and teenagers and they like me. We feel an affinity for each other. They’re unfinished and their taste in literature is still forming. I’m unfinished and my taste in literature is still forming. I think it’s important, though, not to dumb down my YA writing. It’s condescending to think that teenage readers can only handle short sentences, simple words, and totally frothy books. STRANDS OF BRONZE AND GOLD might be challenging to some young readers, but they’re up to the challenge. It’s a Gothic novel, in the tradition of classics like JANE EYRE or WUTHERING HEIGHTS. I love the idea of introducing teenagers to this time-honored genre.

Where do your ideas come from?

Where do your ideas come from?

Everywhere. My second book, THE MIRK AND MIDNIGHT HOUR, which will be released in March 2014, partly came from a story I’d been conjuring up in my daydreams for years. I would tell it to myself as I was falling asleep. Other ideas come from things people say to me or that I overhear, and something about their words will zing into my mind as if it’s especially important. I have written pieces that came from dreams. “Mystical Linguini” was a short story I wrote for a magazine that came about because that title popped into my head and I had to create a story to fit it. Sometimes I’ll be reading a book and one particular line will start a chain of thinking that turns into a new story. I’ll think, If I had written that I would have made that character stow away on that ship and end up in New Zealand, or something like that, and a new story is born. I have a file box full of one-sentence ideas. I will never have enough time in this life to write even a small portion of them.

How did “Strands of Bronze and Gold” come about?

When I was about eight years old, I read the story “Bluebeard” in an old Grimm’s fairy tales book. When I was deciding what to start writing next, I ran across an allusion to it in another book. (It was in EMILY OF NEW MOON, and it mentioned “Bluebeard’s chamber.”) Immediately I wondered how often it had been retold because I wanted to do it. I looked it up and could only find a few short stories, although since then I’ve been made aware of some other versions.

What is it about Bluebeard’s tale that is so fascinating?

It’s so different from most fairy tales. There’s no magic in it, except for the bloody key (which I omitted from STRANDS—just didn’t fit in), and it’s creepy. Most of us enjoy reading something with a shivery touch of the macabre, as long as we know we’re safe and cozy while we read it. Really “Bluebeard” is a Gothic mystery about a serial killer that somehow found its way into fairy tales. There’s the mysterious, fabulously wealthy master of a gorgeous house, his terrible secret, and the young girl who, in spite of her innocence manages to thwart his plans and save herself.

Did you find it difficult to make the tale your own?

JN: No. As soon as I started writing, it was mine. It’s so fun to be an author because you have All Power. I could place the tale wherever and whenever I wanted to. I could summon up lavish surroundings and gorgeous clothes. I could dream up whatever secondary characters seemed to fit best. I was about to mention that I could also make Sophie and Monsieur de Cressac say and do whatever I wanted them to say and do, but that isn’t quite true. Characters have a way of becoming people with minds of their own, separate from the writer.

How did Sophie’s character evolve?

How did Sophie’s character evolve?

There were certain facets of Sophie’s character that I had to use, such as her age (she had to be old enough to marry), her curiosity (she had to poke her nose into her guardian’s past and his home), and her naivety (Monsieur de Cressac had to fool her for a long time). I decided she and all the wives ought to have red hair as a foil to de Cressac having a blue-ish beard. Sophie needed to be a bit vain and materialistic in the beginning, so that her head could be turned by her guardian’s compliments and gifts, along with Wyndriven Abbey’s unaccustomed luxury. Even though she starts out innocent and protected, Sophie is a feisty, clever girl. Gradually, as she gets to know Monsieur de Cressac better, she begins to feel suffocated by his controlling nature and his gifts, and realizes that he wants to isolate her and keep her only to himself. As she comprehends this, and as she learns more of her guardian’s past, she grows up quite quickly. She ceases to care for fine clothes and fine things, she gains a feeling of responsibility for other people—the servants and her family—and longs to help them. She makes the sacrifice of becoming engaged to de Cressac in order to help her family.

Why did you choose to set the novel in 1850s Mississippi?

The 1850’s was a given. There’s something in me that is homesick for the 1800’s and I’ve always enjoyed historical fiction set in that time period. I actually started out by setting it in 1850’s Europe. Then one morning I woke up with the thought in my head that I needed to set it in Mississippi. At the time, we had recently moved to Ontario, Canada from small town Mississippi and I was missing it. (And guess what? I have just learned that we are moving back to that same small town in a month or so!) It turned out to be a good setting for several reasons. It needed to be a time period when females had few options. It also needed to be a time and place when a wealthy man would have great power over a great many people, and 1850’s Mississippi was such a time and place. Monsieur de Cressac had the power of life and death over his ward and over his servants. In that setting no one was near enough or had enough authority to question it.

How is “Strands of Bronze and Gold” different from other novels?

Every author has their own voice and puts their own individual touch on their work. A few aspects stand out in STRANDS. It has a less frantic pace and is more atmospheric, character-driven, and psychological than your average YA adventure novel—a tribute to the Gothic classics for adults that have gone before. I allowed myself to be lavish with descriptions because I enjoy books like BEAUTY, by Robin McKinley, that paint beautifully-written images with words. The pre-emancipation setting is also distinctive. Most writers nowadays shy away from that setting because slavery is such a painful and delicate part of American history. I tried to handle the issue with sensitivity and still to be realistic. In fact I studied many slave narratives, which are interviews held with former slaves during the Great Depression, in order to authentically depict it. In addition, Sophie and de Cressac’s relationship—how he draws her in, uses mind games, and tries to take her over completely—is something that should be addressed more than it is, because it’s such a current and common danger for females.

What are you working on now?

I just finished the first draft of the third companion book in the series, tentatively titled A PLACE OF STONE AND SHADOW. It takes place at Wyndriven Abbey in 1867, two years after the Civil War ended. The abbey has been turned into a young ladies’ academy. It deals a lot more with the supernatural than the first two books, because some of the former inhabitants of the abbey do not rest in peace. Right now several discerning beta readers are going over it to help me know what works and what doesn’t.

Looking back, how has your writing evolved?

Looking back, how has your writing evolved?

When I was in seventh grade, my creative writing teacher told me I should try to get published someday. When I was a senior in high school, my English teacher questioned whether I had copied a story I had written—in a way, I was flattered. So, I’ve always had a knack for writing, but it definitely needed to be honed and polished. For many years, I was too busy working and raising my family to do much writing, but my children were so interesting, and they allowed me to understand a variety of complex people much better than I would have when I was younger. Over those years, I did author a human interest column, mostly with family themes, for our local paper. I had a good many stories published in children’s magazines and I wrote a couple of middle-grade books that earned me many nice rejection letters. The newspaper column helped me learn to write about people and the experiences and emotions we have in common. The short stories enabled me to understand the publishing world better and to make my writing more concise and less meandering, since magazine stories may only contain a limited number of words. I’ve been told that rejection is good for us too. After STRANDS was accepted for publication by Knopf/Random House, my editor, Allison Wortche, helped me avoid some common writers’ pitfalls and she has taught me to do more self-editing. Finally, I’m braver nowadays than I was when I was younger—I’m not so afraid to reveal myself in my writing.

Is there a particular book from your own youth that still resonates with you today?

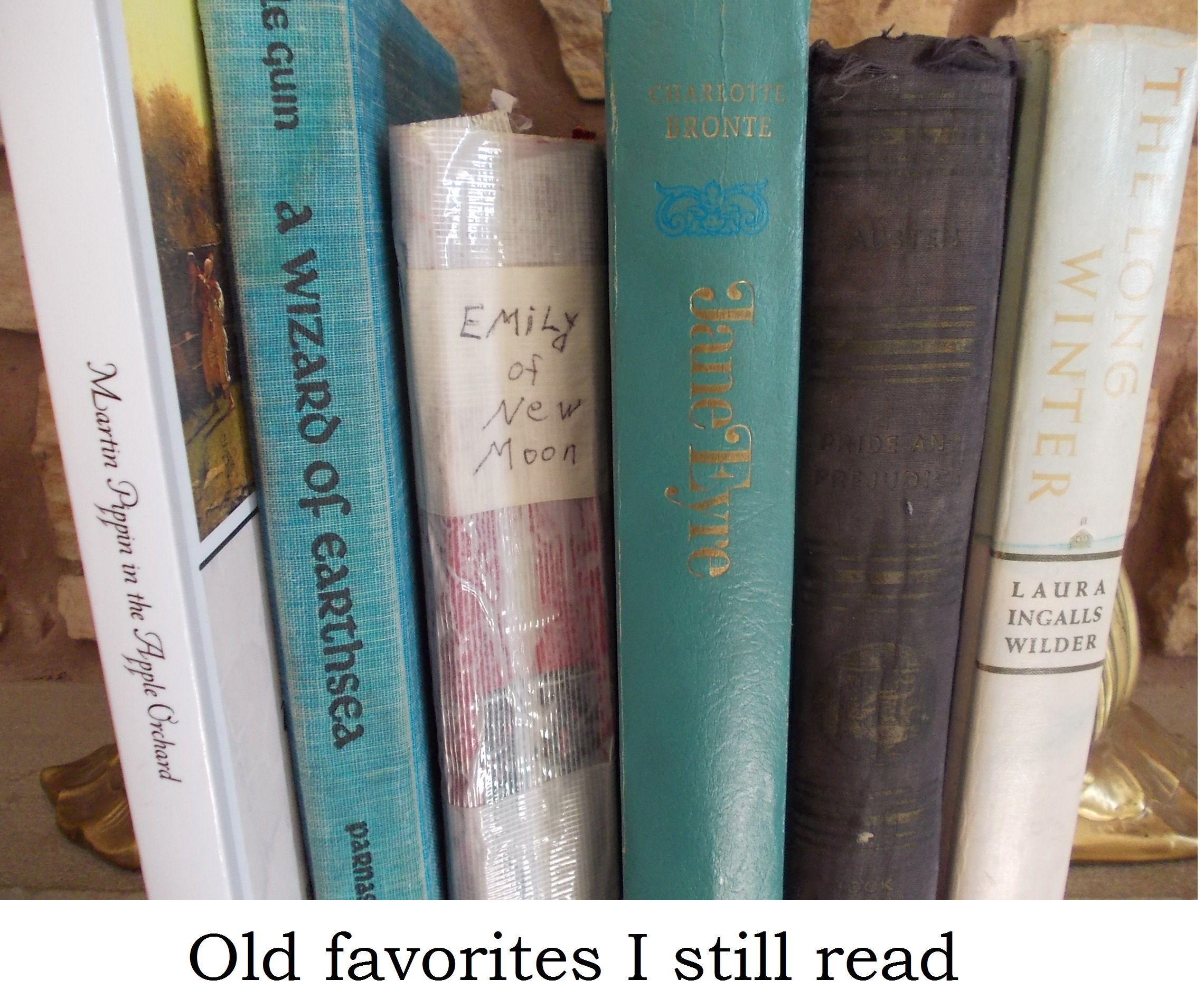

JN: There are lots of them—I’m very loyal to all the books I loved back then, and re-read them occasionally—but I’ll try to narrow them down. I read THE LONG WINTER, by Laura Ingalls Wilder, every winter because it puts me in a snowy mood. Both Eleanor Farjeon’s MARTIN PIPPIN IN THE APPLE ORCHARD and L.M. Montgomery’s EMILY OF NEW MOON have such beautiful writing that I re-read them often. I devoured PRIDE AND PREJUDICE and JANE EYRE when I was in the fourth grade, and they’ve never lost their magic for me. And A WIZARD OF EARTHSEA, by Ursula K. LeGuin is so creative and atmospheric that it serves as a model of the kind of fantasy books I would like to write eventually.